The Secrets Behind Specialist Jobs in Animation and VFX

UTS Animal Logic Academy, have put together a breakdown of some of the key specific industry roles, from industry pros, to help you prepare for your future job in Animation and VFX.

UTS Animal Logic Academy, have put together a breakdown of some of the key specific industry roles, from industry pros, to help you prepare for your future job in Animation and VFX.

If you’re new to animation, visual effects and visualisation, or even if you’re already working in the industry, one thing you might notice is how many different types of roles and job titles there seem to be—all those names in the end credits, for example.

UTS Animal Logic Academy and Ian Failes from befores & afters, have put together a breakdown of some of the key specific industry roles, from industry pros, to help you prepare for your future job in Animation and VFX.

As it happens, UTS Animal Logic are also recruiting for specialised roles for next year’s Master of Animation and Visualisation. Applications are now open. Visit this link for more information.

So, what does a modeller do, exactly? What knowledge, skills and abilities are required to be a lighter? Or, what things do you need to know to get into FX? These, of course, are just a few of the vast number of roles available.

In this article, befores & afters spoke to key animation and VFX professionals from a number of Australian studios about what some of the specific roles are in the industry, what’s involved in each, and the things you can do to be serious specialist in that area.

It’s important to note that there are many other individual roles and departments involved in VFX, animation and visualisation not discussed here, but these do represent several of the core roles across typical studios.

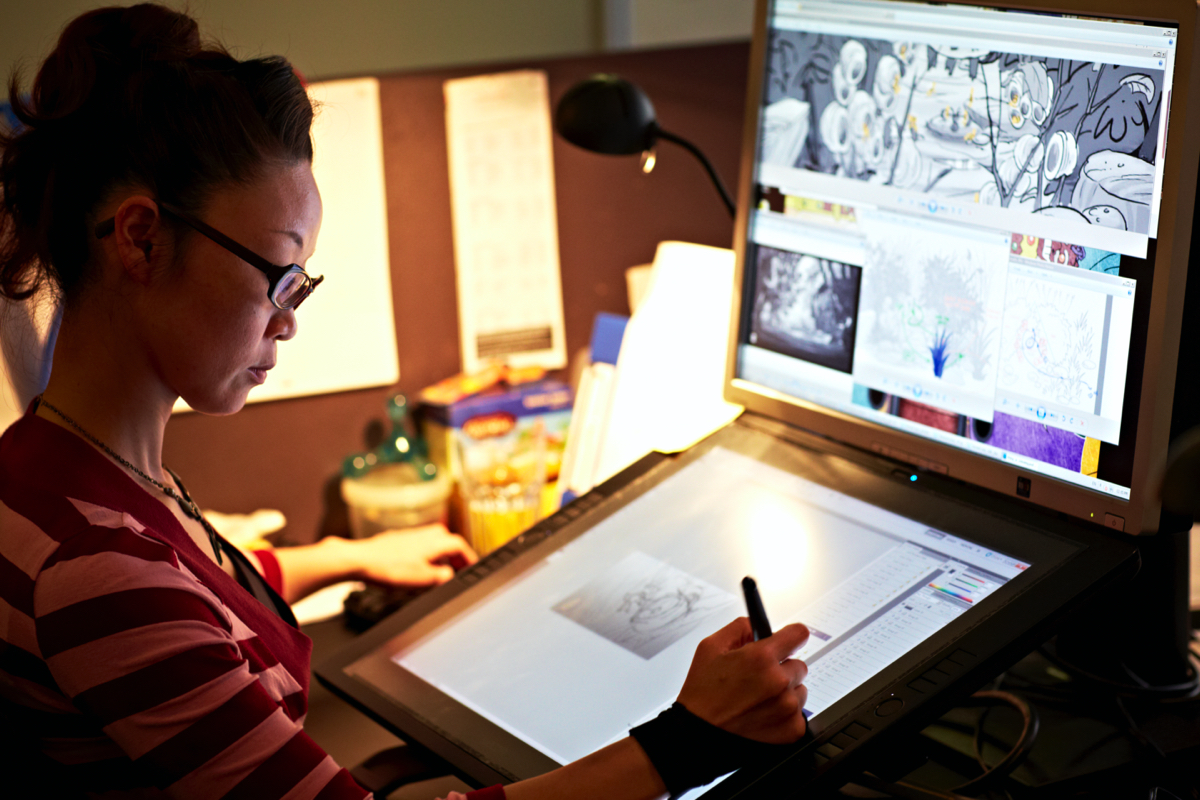

What’s the film going to look like? How is what’s written on the page or what the director envisions going to be brought to a ‘visual’ life? This process typically happens within a studio’s story and art department. The art department tends to be made up of a production designer, art director, concept artists, character designers, story and storyboard artists, graphic designers and matte painters. The range of tools they use stretches all the way from pencil and paper to 2D and 3D programs.

Art director Felicity Coonan is a member of Animal Logic’s art department. Coonan, who has credits on films such as The LEGO Ninjago Movie and Legend of the Guardians: The Owls of Ga’Hoole, will work closely with the production designer on a project to manage the art team.

“Animal Logic’s art department designs the characters, environments, vehicles, creatures and props. This design process involves daily reviews with the art director, production designer and sometime the director. Once approved, we clearly communicate the intention of the design and deliver them to the assets department and other downstream departments. As the production goes on, we have creative oversight of those assets to make sure they are consistent with the visual ambition of the film."

“Most people in the art department have probably studied fine arts or digital media, and can draw well, but the real ‘superpowers’ that make them extra special are curiosity, communication and collaboration. We love our artists to have a curiosity for the larger world – culture, art movements, architecture, music – whatever they’re into, and to be able to express their ideas. Creative collaboration is a daily essential and being able to freely give and take critique is a healthy part of that process.”

“Everybody at Animal Logic is invested in your success,” adds Coonan. “You tend to be fed the work that you’re good at. So, if you are a bit shy and you’re a brilliant renderer, then you might become a finishing artist in the concept department. If you are a great communicator and you love organising, then you might become an art director because that’s where you’ll naturally thrive. Not everybody has to be a huge people-person or a leader, it’s more important to be channelled towards what you’re good at and love.”

A lot of the planning process for an animated feature or a visual effects sequence can happen inside the art department at a studio, especially via concept art and storyboards. But previs, or previsualisation, is also a step in the process that is all about planning. Now also commonly referred to as ‘visualisation’, previs involves crafting scenes with low resolution CG models to help establish the main story beats. The key consideration is being able to change things quickly—and therefore less expensively—since this is still early in the process.

Previs can also involve several related disciplines; pitchvis, techvis and postvis, which all come in at different stages of production, again to help flesh out the story, quickly. For many years, previs was largely the domain of artists working in Autodesk’s Maya, sometimes only rendering out ‘playblasts’ from the software, but it has in recent years become much more sophisticated with virtual production techniques and game engine rendering. Artists working in the field tend to need to know about cinematic language and some technical details relating to cameras and shot composition, since they are helping to design what will become final animated or live-action shots.

Layout, meanwhile, could be considered a somewhat related area to previs, in that it is similarly about shot design. However, layout artists are—for both animation and in live-action VFX—working to resolve the ‘final’ shot framing, composition, camera angle, lens choice and camera movement in a scene. Sometimes they may also impart a rough level of lighting. Building on top of layout will be just about every other department in a studio pipeline, so the role is crucial. Again, a good understanding of cinematic language and principles is key.

Everything you see on screen in an animated feature, and anything that forms part of the CG in a visual effects sequence, needs to be modelled. This might be a specific creature or a building, or it could be a vast environment, and even the tiniest details like pores on a digital human’s skin surface. Modelling artists take concepts, photos, 3D scans, real-life reference and their own creativity to build digital models in 3D, typically with tools such as Maya, ZBrush and Mudbox.

Josh Bramley, an asset supervisor at Flying Bark Productions, breaks down the roles that modellers take on at his studio. “A Flying Bark modeller is responsible for all aspects of their model as it travels down a pipeline. The model should be sculpted to match the design / concept from the client and function logically based on that design. For example, a piston should function like a real world piston, made up of many parts and not just one block of clay.”

“The topology should be clean, logical, with zero nGons and not excessive,” Bramley continues, noting that the modeller should “always be communicating with the rigging department to achieve the most functional flow of topology. Also, you need to produce clean logical UVs, laid out based on the topology of the object and materials so a texture artist can easily identify and paint the asset.”

What makes a good modeller? Bramley comments that it helps to be willing to learn new skills and methods, be adaptable to the situation and be able to take on endless feedback with a smile. Bramley also notes at Flying Bark, which works in both 3D and 2D animation, modellers there come from a wide background and skillset. “This includes,” he says, “people straight from design colleges and universities studying art of some form, people who have worked in a variety of retail and hospitality industries, tradies, military personnel and self-taught freelance artists of various mediums like painters and clay sculptors.”

The CG models which the modelling team build are usually just an underlying structure. What they need now are surfaces like skin, or car door paint, or rocky outcrop markings, depending on the model. This work in animated features and in VFX is handled by texture artists, who essentially rely on digital brushes to give 3D models their surfaces, or textures.

These days, vast libraries of materials, such as those from Quixel Megascans, are available from which to choose textures from, especially for everyday things like metals and plants. Tools like Foundry’s Mari and Adobe’s Substance suite are the most common ones used for texturing.

The other thing models often need to do is, well, move. And that isn’t just if they are a CG lion or a CG digital double. Vehicles or spaceships that need to explode are often rigged, too. This step in the process, handled by riggers, involves building an underlying skeleton with joints on the models, enabling animators to create performances.

Riggers typically need to understand anatomy, to some degree, and give consideration to key story points that need to be hit with certain creature movements, while also considering the complexity of rigs in the animation or VFX pipeline (‘heavy’ rigs and models can slow down animation).

The artists responsible for ‘moving’ CG models are animators, and, of course, they do more than just add movement. They give creatures and characters a personality, or they make a spaceship have dynamism. In VFX and animation, animators work predominantly in tools such as Autodesk’s Maya and 3ds Max, Blender, Maxon’s Cinema 4D and a host of others. Right now, there’s somewhat of a resurgence in stylized animation, even to the point of combining 2D and 3D looks.

Inside a VFX and animation studio, animation departments are usually broken up into teams or structures. At Animal Logic, for instance, a typical structure sees teams overseen by a lead animator, who reports directly to an animation supervisor. Under the lead animator are a mix of senior animators, mid-level animators and junior animators, and production co-ordinators.

“We generally have teams of 8 to 10 people, and we try and build these so that any team can handle any kind of work,” outlines Animal Logic animation supervisor Simon Pickard, who most recently worked on Peter Rabbit 2. “We sometimes break off animators to tackle complex characters or scenes in the film, but we try and balance it so that each team works across a pretty broad scope of work.”

Animators at the studio come from a diverse array of locations and educations; Pickard pinpoints online courses like iAnimate and Animation Mentor as being institutions where animators have learned key skills before starting there. “They’ve also come from the UTS Animal Logic Academy, and we see some start at other studios like Fin Design or Flying Bark, before coming here. It’s a very close community so animators tend to work at most of the major studios over time. As well, we hire animators from across the world for our Sydney and Vancouver studios.”

A good animator, according to Pickard, can be a naturally gifted artist, but can equally be someone who has crafted and honed their skills over many years. “In my experience, you have your natural animators who are almost kind of born with this power, this skill, and then you have the animators that work, and work really hard at it. What’s actually consistent between both, in animation, is ‘observation’. The people who really get animation are continuously observing their work, other people’s work, the outside world. It’s bringing these experiences together and storing all the little things that you observe in the world and then drawing from them when we’re working on our characters.”

Elements such as water, fire, snow, explosions and ‘magic’ all tend to fall under the realm of ‘FX’ (short for effects) at an animation and visual effects studio. These things need simulation, often using tools like SideFX’s Houdini to replicate real-world phenomena or create elaborate ‘sims’ on screen. Of course, many other tools can be used for crafting FX, such as Maya, Blender and an array of real-time game engines including Unreal Engine or Unity.

“FX artists are usually responsible for animation or assets that would be too time consuming to create through standard animation or modelling tools,” details Matt Estela, a senior Houdini artist at RYOT. “The most obvious of these would be things like fire, water, destruction, particles, but over time FX has come to involve extending sets, crowds, volumetric elements and character effects like muscle, skin, cloth, hair and fur.”

Estela previously worked at Animal Logic in the FX department. On The LEGO Batman Movie, one aspect he was tasked with was a ‘riff’ on what The Phantom Zone might look like. “I did LEGO-animated truchet tiles, others did LEGO hypercubes, the winner was LEGO bizmuth crystals. Another time I prototyped what hybrid photoreal and LEGO rain might look like, which went through an alarming amount of options, while at the other end I came up with an automatic way to jiggle leaves in a tree for the first Peter Rabbit film. Lots of different fun challenges.”

Estela’s view is that FX has become such a broad department, one that encompasses a large number of technical and creative roles, that the kind of person suited to becoming a good FX artist is hard to pin down. “I’d say two common traits are a curious mind and an eye for natural phenomena. New FX are rarely formed out of thin air, the ability to research ideas quickly, find prior art, related fields, good visual reference is important, but also being able to look at any reference you find, compare it to your own work, and know how to improve your work based on the reference.”

‘Matte painting’ turns out to be one of those hang-over terms from the earliest days of visual effects where environments were painted on glass, sometimes even leaving an area—a matte—for live-action footage to be projected and make up a bigger scene. The name has continued into the digital era, with animation and VFX studios both making extensive use of matte painting to build out worlds.

Today, matte paintings and environments are made up of 2D painting, 3D models and everything in between. A painting could take shape, for example, in Adobe Photoshop, all the way through to being built up in tools like Maya and Isotropix’s Clarisse, and composited in Foundry’s Nuke.

Once models have been fleshed out with textures and animated, they go through the lighting process. Effectively, they need to be lit just as if they were an actor on a sound stage. This will be to match them into the environment, whether it be live-action or fully computer generated renders, and also to establish certain tones or moods, again, similar to real cinematography. Tools like Foundry’s Katana and SideFX’s Houdini are often used to craft large-scale lighting on animated features and in big VFX sequences, since there will be many shots that need lighting to be consistently applied.

“There are three main broad functions in lighting,” says Mr. X lighting lead artist Hazel Gow. “The first one is collecting all the data from upstream departments. The second one is where it comes down to the actual lighting part of the job, which involves matching the CG elements that we have to the film plate that’s been shot on set, and that involves matching with reference and matching the on-set lighting that we did at the day. Then once that’s done, you go through rounds of creative notes and iterations with either your internal supervisors or the actual clients themselves.”

Gow, who has worked on films such as Mortal Kombat, Cats and Dora and the Lost City of Gold, believes that the best kind of lighting artist is one who’s organised. “We deal with so much data, it’s very easy to get lost and overwhelmed with information. You’re on a production schedule, you’re at the mercy of not having time. In order to give yourself the time to do the craft and get that creative output, you have to be as organised as possible to give yourself the best chance at getting your best work as well.”

Lighters come from different backgrounds, too, notes Gow, who says she’s worked with artists who studied industrial design, graphic design, visual art or computer science (an area she studied herself). “We also get a lot of cross-department people coming, say from lookdev or FX, where they had found their strength and then been able to apply it in a different discipline.”

You can think of compositing as (almost) the final stage in an animation and VFX pipeline. It’s where compositors take all the different ‘layers’ for a shot—creature and character renders, FX, matte paintings, live-action—and bring them together, often fine-tuning the elements and lighting to make it all work for the scene.

A good compositor is looking to make it appear that all those layers work together seamlessly (and in live-action VFX, especially, to make it look as if the shot was actually filmed for real, without any compositing done at all). The premium tools relied on for compositing are Nuke, Blackmagic Design’s Resolve/Fusion and Adobe After Effects.

The technology on which an animation and VFX pipeline run needs to run smoothly, otherwise a project can be held up. With so many parts to a pipeline—artists, network, software, etc—pipeline roles differ at different studios. Dedicated pipeline technical directors (TDs) often work at several levels to ensure the pipeline ‘works’. Sometimes their roles can extend to R&D (research and development) too, in terms of new tools and new pipelines for achieving shots.

Flying Bark technical animator Jade Willems is one artist whose role covers a large part of the production pipeline at the studio. “We help the co-ordinators track their teams shots from modelling through to lighting. If rigs are breaking for the animators, we test and send detailed reports to rigging to fix the issue. If tools are breaking, we liaise with the TD’s to test and get them working on the animation floor. When renders are failing on the render farm, we troubleshoot the issue and get them ready for director review.”

“We also work closely with the assets department to ensure that everything turns up in the right spot for final QC (quality control),” adds Willems. “We do the final QC pass, to clean up the animation in preparation for lighting. This includes post sculpting motion, to give the final pose of a character a better shape.”

Willems recommends the technical animation role as a great way to enter the VFX, film and animation industries. “We all come from a generalist background, but have strengths/interests in one area of production. I studied all areas of CG when I graduated from high school and went on to work in television commercials for a long time. However, I always wanted to work in film, so becoming a TA has allowed me to use all the skills I had learnt over the years, and gain valuable knowledge about all departments involved in creating a feature film. It’s a great stepping stone into the direction you wish to go, I have seen TA’s go on to become rigging artists, TD’s, modelling artists, animation directors and CG supervisors.”

Production co-ordinators are vital at visual effects animation studios. They help to keep the ‘engine’ of the studio running smoothly on individual productions, ensuring that team members in production and on the creative side have all the information they need to make the content they’re being asked to make. Co-ordinators capture information and push information around the VFX and animation pipeline.

To do this, production co-ordinators typically rely on in-house databases or spreadsheets, as well as off-the-shelf production tracking tools like ftrack or Autodesk’s Shotgrid. Being well-organised is a critical part of the production co-ordinator role.

So, there you have 12 different roles and areas within the typical animation and visual effects pipelines. If you’d like to embark on any of these roles, consider studying at the UTS Animal Logic Academy which offers an accelerated 1-year Master of Animation and Visualisation. As part of the course, students specialise in one of the roles mentioned in this article, helping them to launch their careers in industry by taking them from generalist to specialist.

Brought to you by UTS Animal Logic Academy:

Originally published by befores & afters. This article is part of the befores & afters VFX Insight series.